Have you checked out Mind The Gap yet? It’s a blog written by Stephen Wilkins, MPH. He’s interested in physician-patient communication that’s both personal and professional. His most recent post (Via Health Works Collective) addresses the issue of relevancy, something that you might immediately think, that? Oh, I know that. But the truth is, if you’ve been a healthcare professional running through what Michael Tetreault called the “hamster wheel” then you might have developed some bad communication habits.

Think of it like this, if a patient comes in because their chest hurts, then make sure first and foremost you listen and communicate what might be causing this ailment, and what might need to be done to make them feel better. Focus on why this might not be an issue, and why that is the case. Even if it’s a hypochondriac situation, don’t brush it off. Your patient might leave worried, feeling that you’re unsympathetic.

And it’s this feeling of antipathy that might come back to bite you. In Malcolm Gladwell’s book, Blink: The Power of Thinking Without Thinking, he shares data suggesting that more mistakes is not what will get doctors sued more often. No, it turns out poor communication has a higher correlation with malpractice lawsuits. There are even cases documenting patients who don’t want to sue a doctor they like. In the case of an undesirable outcome, they actually insist on suing the doctor that didn’t listen to them, or made them feel rushed. So what’s the moral of the story? Take time to talk to your patients, and take time to make sure you’re communicating what’s relevant to them.

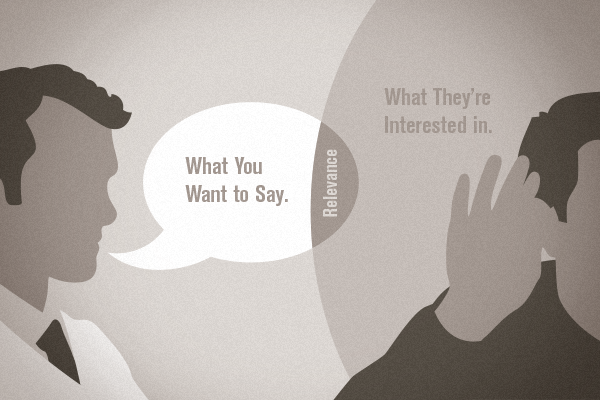

A side note: the communication breakdown that Wilkins addresses is admittedly exacerbated by the industry’s fast-paced scheduling. The fact is that the average primary physician only spends 5-7 minutes with a patient. If an older patient has five ailments, there’s literally no way to address them all in that brief span. Now imagine they are really concerned with one of those ailments specifically. However, you’re more focused on administering a new test they are scheduled for, which they had no prior awareness of. This creates the type of scenario where you’re talking about something important, but not relevant. And that’s the challenge. Not only does the conversation need to be relevant to a patient’s health, the dialogue needs to be relevant in their minds, too. Because, at the end of the day, we’re all just people.